High Frequency Words: Stop Memorising, Start Mapping

Why High-Frequency Words Should Be Taught in a Logical Sequence

If you’ve ever been told your child needs to just memorise high-frequency or “sight” words like said, the, or was, you're not alone. For years, many schools and programmes encouraged rote memorisation of long word lists, with flashcards and repetition being the go-to strategy.

But here’s the good news:

There’s a better way—and it actually helps your child become a stronger, more confident reader.

🧠 What Are High-Frequency Words?

High-frequency words are the most commonly used words in the English language. Children see them again and again in books and in their own writing. Words like it, in, he, and go appear early and often.

Some of these words are easy to decode (sound out). Others contain trickier spellings—but most are not truly irregular.

❌ The Problem with Memorising

Trying to get a child to memorise 100+ words by shape or visual memory is not only exhausting—it often doesn’t work. Words that are memorised without understanding are easily forgotten, especially when children are tired, distracted, or reading full sentences.

Memorisation also doesn’t help your child with unfamiliar words—they’ve learned to recognise only the words they’ve been shown, not how to work out new ones.

✅ A Better Way: Structured, Decodable Word Learning

Research shows we should teach high-frequency words using phonics and sound mapping—starting with words children can fully decode using the sounds they already know.

For example:

In, it, is, at, on – all regular CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) words

He, me, be – simple words with long vowel sounds

Can, not, up – early phonics-based words

Instead of memorising a list, children learn to sound out, map, and write each word, building real understanding and long-term memory.

🔍 But Isn’t English Spelling Irregular?

English spelling has a reputation for being chaotic—but it's more regular than you might think.

Studies show that over 80% of English words follow predictable spelling rules once children are taught about phonics patterns, syllable types, and a few common exceptions.

Even tricky words like said and some have predictable parts:

Said → “s” and “d” are regular; we remember that “ai” says /e/ just in this word.

Some → “s” and “m” are regular; the “o” makes an /ʌ/ sound (as in son).

These words don’t need to be memorised entirely—just the irregular part, often called the "heart part". We remember that bit “by heart,” but still decode the rest.

📘 Teach Words in a Meaningful Sequence

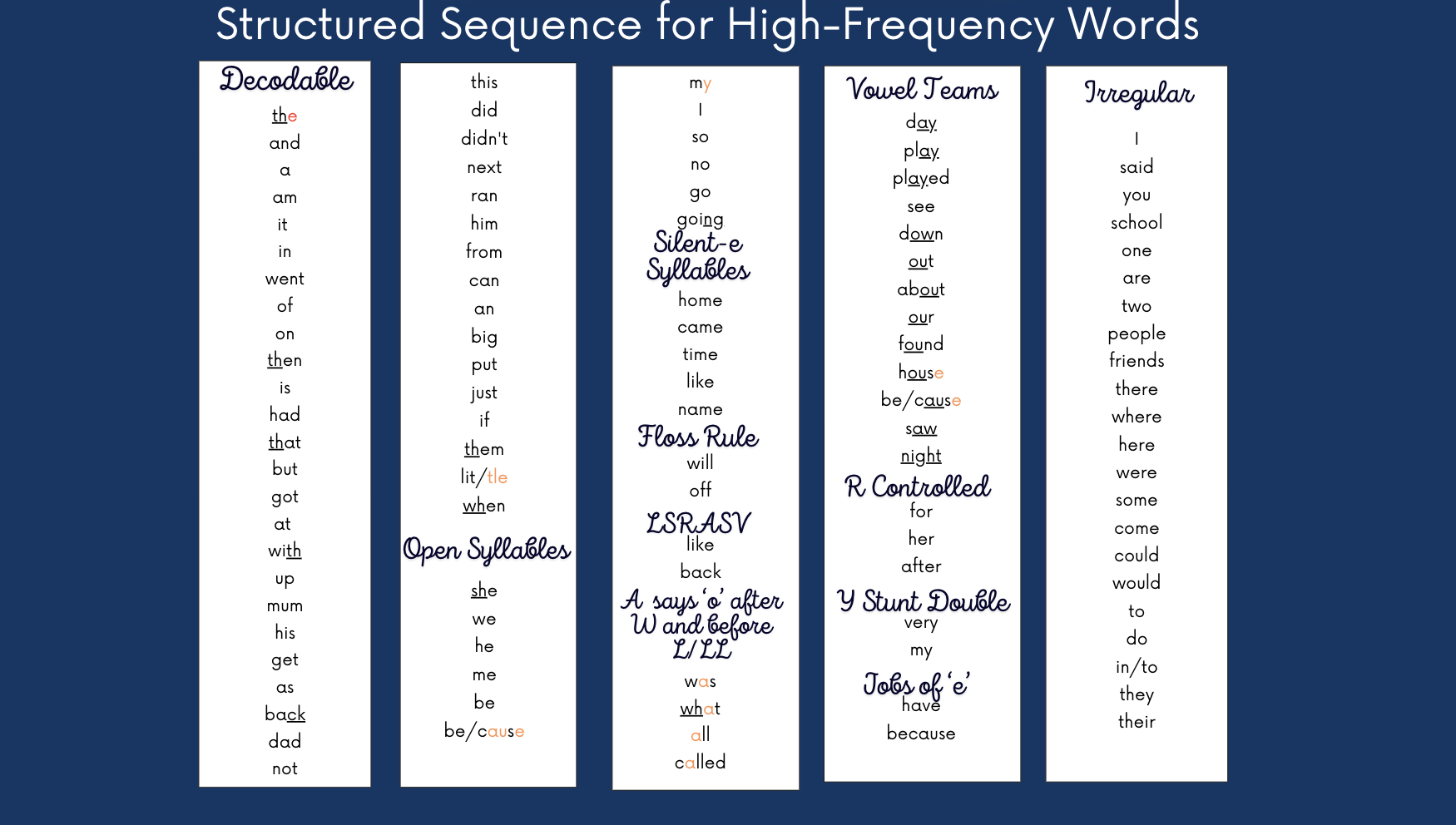

At ParentEd, we organise high-frequency words into a clear learning sequence:

Start with fully decodable words

Introduce trickier words only after the regular sounds are known

Revisit tricky words in reading, writing, and spelling activities

This helps children feel successful early on, which builds confidence, fluency, and motivation.

💡 Try This at Home

Focus on 10–12 decodable high-frequency words at a time

Practise reading and writing the words

Talk about the sounds, not just the letters

Highlight the tricky part (vowel teams or silent letters) and explain it simply

Use games, whiteboards, fridge magnets—make it fun and repeat often!

❤️ Final Thought

Teaching high-frequency words doesn’t have to be a memory test—it can be a structured, stress-free, and meaningful part of learning. By teaching words in a logical sequence, you’re not just helping your child recognise a list—you’re giving them the tools to become confident, independent readers.

And that’s a gift they’ll carry with them for life.